On Friday 24 February, the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) announced its decision to greylist South Africa. The decision has had both a reputational as well as economic impact on the country. With this said, the true impact of the news will only be revealed with time.

Background

In October 20211, the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), a global money laundering and terrorist financing watchdog, identified key weaknesses in some of South Africa’s financial regulations. South Africa was subsequently allowed to address these weaknesses and report back to the FATF as to how these weaknesses would be addressed (within roughly 12 months).

Of the 40 areas covered in the report, South Africa was found to be fully compliant in only three areas, largely compliant in 17 areas, and partially compliant in 15 areas. The five areas in which South Africa was deemed to be non-compliant include –

- Targeted financial sanctions related to terrorism & terrorist financing

- Non-profit organisations

- Politically exposed persons

- New technologies; and

- Reliance on third parties

The main issues identified include concerns around money laundering, terrorist financing, generally high levels of crime and corruption, as well as the high levels of cash used in our economy (combined with a large informal economy which includes cross-border remittances).

The term “greylisting” is actually an external term and not necessarily a term used internally by the FATF itself. Officially it’s referred to as “jurisdictions under increased monitoring”. Countries on this list are under increased monitoring and actively work with the FATF to address strategic deficiencies to counter money laundering, terrorist financing and proliferation financing.

Currently, this list includes countries such as Albania, Barbados, Burkino Faso, Cambodia, Cayman Islands, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Haiti, Jamaica, Jordan, Mali, Morocco, Mozambique, Myanmar, Panama, Philippines, Senegal, South Sudan, Tanzania, Türkiye, UAE and Uganda. The most recent countries to have been removed from the grey-list were Nicaragua and Pakistan.

This is not exactly a list of countries a well-functioning economy would aspire to be part of. ‘You are the company you keep’ and ‘guilty by association’ – as the old sayings warn, right? What is also striking is the large number of countries from Sub-Saharan Africa.

There is also a blacklist, which contains only two countries, namely Iran and North Korea. These countries are deemed to be high-risk jurisdictions, that are not actively engaging with the FATF to address these deficiencies. The key difference between the two lists is effectively the willingness to participate actively in addressing the vulnerabilities identified.

So, what has South Africa done so far?

In a recent presentation to Parliament’s justice committee, national director of public prosecutions, Shamila Batohi, indicated that despite progress being made to address money laundering and terrorism shortcomings, the country was still behind in terms of meeting all the requirements of the FATF.

Parliament passed two acts last year to meet international anti-corruption standards. South Africa’s presentation at the recently held FATF meeting in January in Morocco (a country that was also recently added to the grey-list) was reportedly well received. It seems that 15 out of the 20 legal deficiencies cited by the FATF were adequately addressed. While there are still outstanding concerns, South Africa has certainly made a concerted effort to address some of them and is clearly paying attention and collaborating with the FATF. This should be applauded albeit not enough in the end.

To illustrate using a comparison, when Botswana was originally greylisted in October 2018 its 2017 country report by the FATF found:

– 23 areas (out of 40) of non-compliance

– 14 areas of partial compliance

– 2 areas of being largely compliant

– 0 areas of compliance

Recap of South African figures:

– 5 areas (out of 40) of non-compliance

– 15 areas of partial compliance

– 17 areas of being largely compliant

– 3 areas fully compliant

Botswana was removed from the grey-list only three years later in October 2021. The starting point was very different, with South Africa being in a much better position. Perhaps the country has done enough to avoid being greylisted completely, or if greylisting happens, the time spent on the list could be relatively short.

Impact of being greylisted

Financial institutions such as banks and administration companies have expressed their concerns regarding the impact of being greylisted. This is due to increased turnaround times (for transactions with international counterparts) and/or additional costs (due to enhanced due diligence procedures).

While the FATF standards do not formally require de-risking (avoiding entire classes of customers) or enhanced due diligence, financial institutions are expected to follow a risk-based approach and conduct detailed due diligence on customers from high-risk countries. It wouldn’t be unreasonable to assume that certain institutions would simply choose to avoid doing business with certain clients as opposed to triggering additional due diligence procedures.

We have often seen disparities between capital markets and how economies fare over the short term. To understand what could happen, one should look at these separately. Previous research has indicated little empirical evidence for banks to de-risk and avoid relationships with clients in “higher risk” countries or that investors globally use the FATF grey-list as a convenient heuristic to assess risk when making capital allocation decisions.

A recent paper by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which uses a larger and more recent data set, does find significant negative effects on capital inflows highlighting a decline of 7.6% of GDP (on average). The paper also breaks down the impact on capital flows into underlying components, for example:

– foreign direct investments, down on average by 3%

– portfolio flows, down on average by 2.9%; and

– other investment inflows, down on average by 3.6%.

– All the impacts were statistically significant

– 1% alpha level.

Being greylisted would clearly be negative for South Africa and our President’s well-documented drive to attract foreign direct investment. The study, unfortunately, doesn’t allow for other conditions that might also influence capital flows such as increased bouts of loadshedding etc.

There are already a significant number of idiosyncratic risks prevalent in South Africa. One almost wonders if one more issue (added to the already long list of issues) would have an impact. Yet, the other side of the equation is that this could be the final straw to break the camel’s back and cause foreign investors to capitulate and abandon SA assets entirely. This seems unlikely.

Should South Africa experience additional reductions in capital flows, especially if it persists over the long term, the economy would suffer in the form of reduced economic growth, increased potential unemployment (and by extension inequality) and higher inflation (due to a depreciating currency). On the capital markets front, the cost of capital could potentially increase and domestic financial assets could become less attractive to foreign investors.

Markets are, however, forward-looking so most of the potential effects of greylisting should already be priced in. According to the Reserve Bank’s statistics, foreigners weren’t exactly rushing to buy either S.A. bonds or equities, but quite the opposite – they have been persistent net sellers over the last four years.

The risk is of course that international investors who still have significant amounts invested in South Africa could be triggered by the news to sell domestic assets. This forced selling might be an opportunity for local investorsto benefit from short-term volatility by acquiring cheaper assets without necessarily increasing the probability of suffering permanent losses on capital. This is also confirmed by both authors of the IMF paper as well as Becker and Noon (2008) that found that while FDI and portfolio flows experience similar declines, portfolio flows are more sensitive and tend to reverse after the initial shock.

Other examples

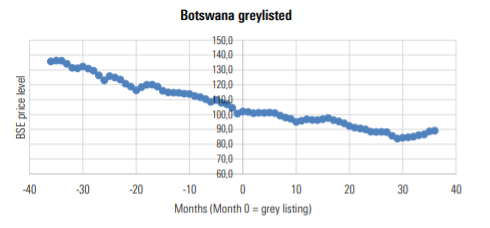

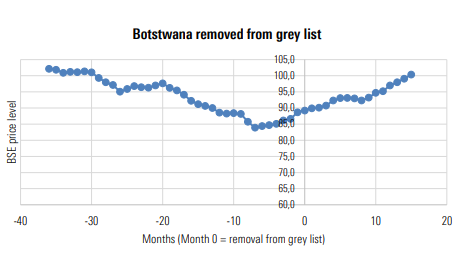

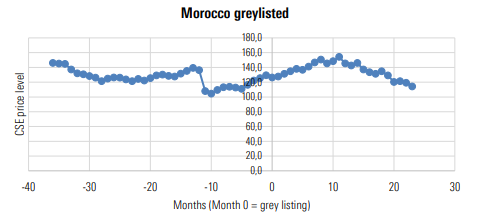

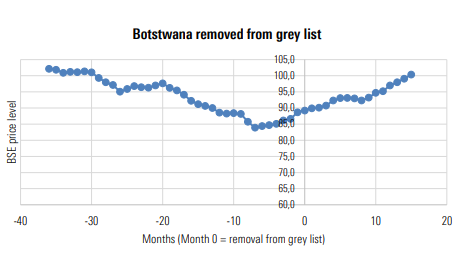

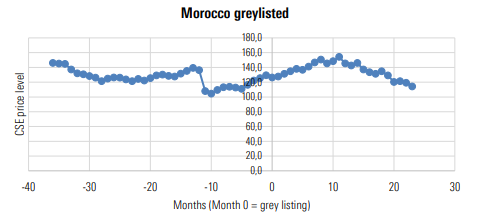

The sample of countries having been greylisted is small, but there are two recent examples on the continent – Botswana (greylisted in October 2018 and subsequently removed in October 2021) and Morocco (greylisted in February 2021). The below graphs indicate the reaction of their respective domestic stock markets to being greylisted:

In the case of Botswana, one could be tempted to conclude that equities indeed respond to a greylisting, however, as can be seen from the Moroccan example not so much. Besides that, one would have to isolate the effect of greylisting from other risk-off events. For example, the drawdown exhibited 11 months before Morocco was greylisted was due to Covid. Once again this is too small a sample to draw any meaningful conclusions from.

What about the European Union (EU)?

The EU adopted a new methodology in 2020 that relies significantly on FATF’s greylisting, however, unlike the FATF the EU doesn’t consider any ‘grey areas’. Countries either do not pose a risk to EU member countries or do, in which case they are added to a blacklist. No consideration is given to those countries that work with the FATF to improve areas of concern as identified.

EU requirements are therefore more onerous and expect member countries to apply a range of countermeasures (from enhanced due diligence measures, which leads to increased timelines and additional costs) to prohibiting EU financial institutions from establishing branches in the specific country. This in turn could lead to decreased foreign direct investments as already mentioned.

The EU methodology also states that it may double-check the work of the FATF or conduct its own assessments when countries are added to or removed from the FATF’s grey-list. There is therefore a potential risk that it might take longer to regain credibility with some of our largest EU trading partners.

Summary

Whilst it is still early it is difficult to make a convincing argument, based on currently available information, that domestic assets will suffer severe drawdowns. Over the shorter term, volatility could be expected, but over the medium term, prices would reflect a myriad of other drivers of returns.

What is perhaps a bit more obvious is the risk that greylisting poses to foreign direct investments, specifically from European countries. It is therefore imperative that South Africa address these weaknesses or shortcomings as identified as soon as possible. The longer the greylisting continues the worse these effects could be which would then inevitably feed through to asset class returns.

South Africa is, however, in a relatively good position, when compared to some of the incumbents on the grey-list and has already shown intent by addressing some of the concerns and weaknesses. The two laws already passed (in record time) should put us on an even stronger footing going forward and re-establish South Africa as an important global participant in the world financial markets.

As always, predicting the future is a mug’s game and with all the other uncertainties and risks currently prevalent in markets, the best approach is to always have a well-diversified portfolio, not dependent on any specific outcome. In addition, working with a trusted intermediary and having a long-term plan in place and sticking to it is possibly the best action one can take.